Apparently through our two articles on the subject, we’ve stirred up the national group advocating for basing the Presidential election solely on the popular vote. (First article here, second article here; comments apparently from a member of that group can be seen in the second article.)

We’re taking the time to highlight the topic because there are several fundamental principles involved. The most important is that these advocates are laboring under the very false assumption that America is, or ought to be, a democracy, not a republic. One element of a republic is to blend direct and indirect representation (see Federalist No. 45), and, often, decisions are made by the people’s elected representatives instead of directly, by the people themselves. The Electoral College is one such representative body within our republican system. It’s important to examine whether or not the Constitution as originally constructed was designed to foster and support democracy. The very opposite is true. Moving away from republic to democracy serves the interest of politicians or those generally desiring to aggregate power and results in a population that is much easier to influence. Unfortunately the media, almost every elected official in recent memory, and a long line of “political strategists” reference democracy constantly as a wonderful thing while the word “republic” never seems to pass their lips. Democracy does not enhance liberty – historically it has devolved into oppressive regimes. Having studied history, the Founders knew that democracy is ultimately the tyranny of the majority and historically a proven failure. (See the article, “A Republic If You Can Keep It“. )

The election of the president by national popular vote would also undermine our federal system. Most people are unaware of the unique design of our republic. It’s called a “federal” system, as opposed to a “national” or “unitary” one. That means that powers are divided among local, state, and federal governments, with some powers belonging only to the federal government, others only to state and local governments, and still others shared by all three. Within each governmental level, powers are then separated between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. In contrast, in a “national” or “unitary” system, power is held by the national, or central government, with the state and local governments serving, largely, as administrative arms of the national power. Many Americans currently complain that Congress regularly acts beyond its powers enumerated in the Constitution, and they decry the centralization of power in Washington, D.C., over matters that were traditionally state concerns. National popular vote will, necessarily, further break down our already embattled federal system by essentially allowing voters in the most populous states to determine the electors in the less populous states. For example1, if all the voters in Nebraska chose candidate A, but the national popular vote chose candidate B, under National Popular Vote the electors from Nebraska would vote for candidate B against the wishes of the people of Nebraska. So, in essence, the National Popular Vote plan does away with the 51 electoral districts (i.e., the states and the District of Columbia) and replaces them with one — the entire nation.

The current effort to move to a popular vote basis for the election of the President is an end-run around the Constitution. There is a legitimate argument to be made that it would require a Constitutional amendment. Beyond that, there is a potential for real trouble resulting from the disenfranchisement of voters and State Legislatures in as many as 37 or 38 states if as few as 12 or 13 populous State Legislatures chose to adopt the plan. We’ve looked into this whole subject further due to the level of interest by the national group and growing number of readers on the articles about it. We have learned that there are mixed opinions regarding whether or not the national popular vote group’s proposal would stand up to a challenge that it is unconstitutional. The group makes the point, correctly, that Supreme Court rulings are clear: the State Legislatures’ manners of choosing electors are “plenary” and “exclusive” (Bush v. Gore, 2000). Wall Street Journal’s James Taranto is convinced the proposal by national popular vote people is not unconstitutional in the sense that State Legislatures do have the ability to choose electors in the manner they see fit. But Taranto goes on to point out the potential consequences. He labels it a political crisis worse than what occurred in 2000:

“Unlike in that case, the Supreme Court would be unable to review the matter because it would be an exercise in plenary lawmaking authority. Challenges in Congress to the electoral vote count would be almost inevitable. Whatever the outcome, it would result from an assertion of raw political power that the losing side would have good reason to see as illegitimate.”

Political crisis? Yes. Worse yet, think Constitutional crisis. We are more hopeful about Supreme Court review; Article III of the Constitution enumerates the powers of the Supreme Court, which includes, “…Controversies between two or more States”. The reason why such crisis could come to a head under the group’s proposal is that it is designed to go into effect as soon as there are enough States involved whose electoral vote tally is equal to 270. This is the imposition of a potential handful of populous States’ will on the rest of the country. If the agenda of the national popular vote group was truly that “every vote should count” why would they support a change that could potentially disenfranchise so many voters and their Legislatures?

Where there are questionable tactics, there are likely questionable motives. We are skeptical regarding the group’s motivation. Again we turn to James Taranto:

“It is a partisan protest masquerading as a high-minded reform. It is a too-clever-by-half attempt to circumvent America’s constitutional structure.”

The group and it’s effort are not only “too-clever-by-half”, they engage in half-fact telling. The commenter on our site stated, “The Electoral College that we have today was not designed, anticipated, or favored by the Founding Fathers but, instead, is the product of decades of evolutionary change precipitated by the emergence of political parties and enactment by 48 states of winner-take-all laws, not mentioned, much less endorsed, in the Constitution.” It sure does sound high-minded and there is actual truth in it. There have indeed been a lot of changes to Article II of the Constitution, there is certainly too much party influence in our electoral process, and winner take all is not in keeping with the original construct.

While well-written and containing truth, the other half of this story is that the proposal does nothing substantive to address any of the problems noted. In fact, it only multiplies them. A genuine pursuit of what was or was not “designed, anticipated, or favored by the Founding Fathers” would include a comprehensive look. First, the founders did consider a proposal to elect the president by national popular vote and rejected it. Second, Wikipedia’s “Electoral College” article includes the following, (with citations here and here):

The design of the Electoral College was based upon several assumptions and anticipations of the Framers of the Constitution:

1. Each state would employ the district system of allocating electors.

2. Each presidential elector would exercise independent judgment when voting.

3. Candidates would not pair together on the same ticket with assumed placements toward each office of President and Vice President.

4. The system as designed would rarely produce a winner, thus sending the election to Congress.

On these facts, scholars have described the intended role of the Electoral College as simply a body that would nominate candidates from which the Congress would then select a President and Vice President.

Under the original plan for the Electoral College, each state government was free to have its own plan for selecting its electors.

While assuredly there are aspects of the system, as laid out above, that we find hard to fathom today, as with other aspects of the Constitution, the framers had their reasons, most particularly among them was the desire to insulate our electoral process from becoming democratized, too influenced by factions, or the result of party processes. An article at the Mises Institute explains in detail 2.

The tactic of including selective facts is not limited to citing the Founders; the primary case made by the national group to elect our President based on popular vote is based on public opinion polling, an element of the very democracy the Founders sought to avoid (See “Majorities Don’t Always Know Best“). Such polls are irrelevant to the matter. But there is another tactic employed as well; the very polling data cited is at best, questionable.

The results of the polls upon which “kohler” relies so heavily are not as straightforward as “kohler” would have us believe. First, it is important to know whether the person or firm conducting the poll is likely to have its own point of view or axe to grind with regard to the issue in question. The pollster who conducted the polls for National Public Vote supporters was Public Policy Polling, “an American Democratic Party-affiliated polling firm located in Raleigh, North Carolina.” While it apparently has garnered praise for its accuracy in election polling, that has no real bearing upon the accuracy of polling it conducts for a private client that is, essentially, a single-issue lobby bent on using the data to advance its political agenda. What happens if the data the polling firm collects does not support its client’s cause? Also, unlike an election poll, ones like that done for National Public Vote are not followed by an actual vote on the issue, allowing the accuracy of the poll to be judged by comparing it to actual vote tallies. In sum, there’s a strong motive to please the private client, with whom the pollster identifies politically, and little chance that “fudging” the data would ever be discovered.

That being said, there are several red flags that arise when you consider the poll results reported for Nebraska regarding the National Public Vote plan, too many to detail here. The major concern, as with any poll, is with the number of persons polled and whether the sample was truly random. Public Policy Polling uses an automated calling method to solicit responses to their polls. Not surprisingly, most polling firms using this method get a lot of hang-ups, cannot know exactly who they are talking to on the other end of the phone when they do get a response, and typically only reach persons who have land-line based telephone service and a listed number.

The survey report states that 800 Nebraskans were sampled. Was this 800 people, total, that were called and some subset of them responded, or did Public Policy Polling keep calling numbers until they had a total of 800 who responded to their questions? The answer to that question is not apparent because NONE of the results are reported in numbers, just percentages. So, for example, if I called 800 Nebraskans, got 100 people to answer my questions, and reported, as Public Policy Polling did in this case, that 74% favored a national public vote for president, what I’m actually saying is that I called 800 people, only 100 answered my questions, and 74 of them favored electing a president by national public vote. The results don’t sound so impressive when they are reported that way, do they?

The advocates of the national popular vote proposal are employing questionable tactics in proposing a dangerous end run around our Constitutional structure. If they have the best interest of the American people at heart and wish for “every single vote to count” and really believe the very polling data they cite, they should have no fear of engaging in a Constitutional Amendment process. After all, if 70% of the American people truly do want to transform into a democracy in this manner, there should be a groundswell of political pressure into which advocates could tap to move a piece of legislation through Congress sending an amendment to States for ratification.

In Article II, the Constitution lays out the manner by which the President is elected and the overall document includes all relevant amendments that made changes to the original language. Whether any of us agree or disagree with those changes, they are the law of the land. To engage in end-runs around the rightful process for making changes is a dangerous practice, particularly if engaged in over and over again; the end result is that the Constitution is rendered irrelevant.

But that is likely the very point of the effort – to move further away from the Constitution without having to make the case to do so.

________________________________

Notes and references:

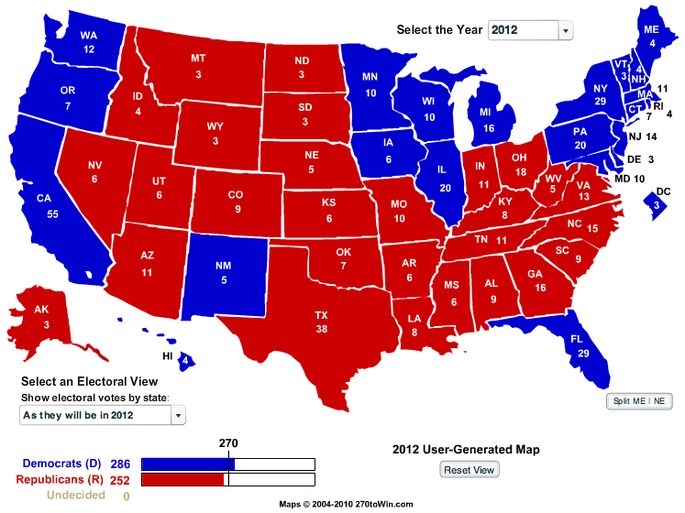

The electoral map graphic was created on the American Research Group, Inc. website with the “Electoral Vote Calculator“.

- The “for example” given here is a link to the Liberty’s Lifeline website where there is an example given as noted in the article. ↩

- There is a lot of interesting information included in the article, but the author is enamored with “experts” and intellectual elitism and conveys it in a way that some readers might find off-putting. ↩

You must be logged in to post a comment.