As of Friday, nine people know the outcome of the states’ lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of Congress’ inaptly named “Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act,” a/k/a Obamacare. The Justices voted at a closed-door conference, but we won’t know what they concluded until June. They and their clerks will spend the time between now and June drafting a written opinion announcing their verdict and explaining the reasons behind it.

Given the chance that the entire Act may be thrown out, I’ve been reflecting on what should be done in its place. In doing so, I’m cognizant of Thomas Sowell’s observation:

“No matter how disastrously some policy has turned out, anyone who criticizes it can expect to hear: ‘But what would you replace it with?’ When you put out a fire, what do you replace it with?”

Ordinarily, I’m inclined to agree with Mr. Sowell. The health reform Congress attempted to effect through this odious Act was . . . well, odious. Doing nothing, however, does not appear to be a practical alternative.

Judging from the title of the Act, Congress had two laudable goals in passing it (and, yes, I’m aware that I’m giving the Democrats the benefit of the doubt here):

(1) Ensuring that patients are protected from insurance practices that may leave them without insurance coverage when they need it most and,

(2) Ensuring that the cost of health care is affordable and, therefore, generally accessible.

But, as the states’ attorneys pointed out in oral arguments this week, it makes little sense for Congress to enact further legislation to fix problems its prior laws have created.

WE WOULD ALL BENEFIT IF GOVERNMENT WOULD SIMPLY GET OUT OF THE HEALTH CARE BUSINESS ENTIRELY.

I realize many readers probably can’t conceive of a health care system that doesn’t involve the government. But you must realize that, just because largely government-controlled health care IS what we have right now, doesn’t mean that was always the case or that it’s impossible to return to a privately controlled system. Medicare and Medicaid did not exist prior to 19651. What did health care look like before those government programs began to drive the system off track?

To answer that question, a story is in order.

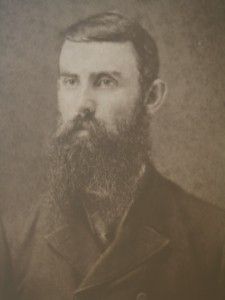

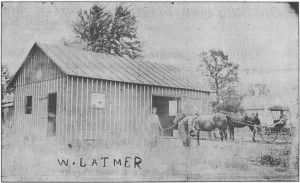

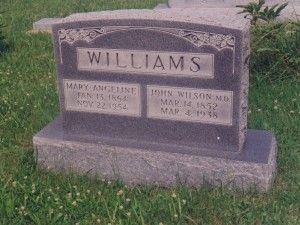

My great-grandfather, John Wilson Williams, was born in 1852 in Midway, Missouri. Unlike many young men of his time, he was fortunate enough to attend school, eventually becoming a doctor. Upon graduation with a degree in medicine and surgery from a school in Keokuk, Iowa, my great-grandfather moved to a rural area in Boone County, Missouri, along with a blacksmith named Latimer and a merchant named Riggs. Latimer opened a blacksmith’s shop, Riggs built and operated a general store, and along with my great-grandfather, they built a small, wood frame building that would become known as Riggs Union Church — Union because it was nondenominational, open to use by any local Protestant congregation and available to itinerant preachers passing through.

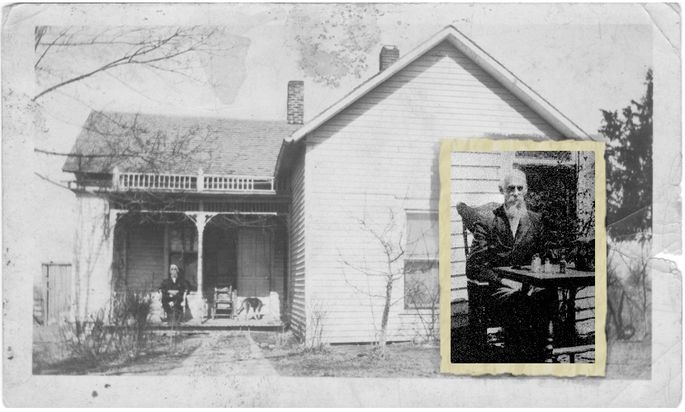

Doc, as my great-grandfather became known in the Riggs community, built his house beside the church and directly across the street from the general store. Although located in “town,” his property was really a small farm where he kept a garden and raised, at various times, horses, sheep, and, on at least one occasion, a rather large flock of turkeys. These activities were necessary in order to support his wife and two sons. His patients were not wealthy. Doc’s account books show he often accepted farm produce in place of money in payment for his services. In fact, to augment his income, Doc kept bees and sold honey.

He had no office, working out of his home. His nearest medical competition was more than 20 miles from Riggs in any direction. Consequently, Doc was always on-call for his patients. During outbreaks of influenza, it was not unusual for him to be out all night in all kinds of weather, making house calls to treat the sick. He was known for his success in treating pneumonia, a disease that often proved fatal at the time. And, of course, he delivered an entire generation of children born to the families in the vicinity. As recently as last year, the administrator of a local nursing home told me that she was surprised how many of the birth certificates of the facility’s patients indicated they had been assisted into this world by Dr. John W. Williams.

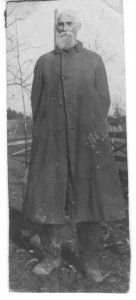

Many of his patients lived in remote locations, roads were dirt tracks, and transportation was literally horse-powered. So, Doc got to those that needed him the only way he could, on horseback. During the fall and winter, he could be seen making his rounds on the back of a large black horse, wearing a long coat, itself made of horsehide, and boots that came to his knees.

Saturday was always a big day in Riggs. That’s the day all the people on the surrounding farms brought chickens, eggs, and other farm produce into town to market. During his 60 years of medical practice in Riggs, weather permitting, Doc kept “office hours” every Saturday, sitting in a chair next to a small table placed on his front porch, his medical bag open and within reach and pill bottles arranged in front of him. People coming into town to shop would cross the street to consult Doc about their ailments.

When Doc was in his 60s, his eldest son, my grandfather, was caught passing bad checks for what, in total, came to a rather large sum of money. Doc attempted to make good on his son’s debts and is said to have ruined himself financially in the process. Regardless of his personal concerns, he continued to serve the Riggs community as a physician for the remainder of his life. The people of Riggs knew Doc’s value and they cared for him in return. For example, once a year, more often if needed, men from the surrounding farms would gather at Doc’s house to cut enough wood for him to heat his house and cook his meals. Their wives would accompany them, bringing food for the members of the work crew that they cooked and shared with Doc and his family when the work was done. When he died at the age of 86, Doc was still so much “their” doctor that they voluntarily took up a collection in the neighborhood and presented his widow with enough money to pay for Doc’s burial.

So, what’s the moral of this story? Am I suggesting that we should return to a barter economy to pay for our health care? Hardly. BUT, I am proposing that we return to a system –

- in which patients and doctors deal with one another on a face-to-face basis with no middle man;

- in which patients know and appreciate the value of the medical care they receive; and

- in which patients bear personal responsibility to pay for the routine portion of their care, with catastrophic insurance to cover exceptional needs, so they have some skin in the game.

All images included in this article, copyright Linda Rohman, all rights reserved, no republication, use GiN’s contact form for information

- Medicare, health insurance coverage for the elderly, and Medicaid, health insurance coverage for the poor, were both “Great Society” programs created during Lyndon Johnson’s term as President, and were actually expansions of Title XIX, the Social Security Act. Medicare is a purely federally funded program, while Medicaid is a VOLUNTARY program funded both by the States and the federal government. Although Medicaid started in 1965, not all states participated until 1982, which was the year Arizona joined the program ↩

You must be logged in to post a comment.