Some men, long dead, are famous for what they DIDN’T do. For example, George Washington almost certainly didn’t chop down a cherry tree and later confess because, as he is reputed to have told his father, he “could not tell a lie.”1 Similarly, there is reason to believe that Benjamin Franklin did not actually fly a kite in a thunderstorm to further his experiments with electricity — although he is known to have proposed the idea.2 As well-accepted as these stories have become, in neither Washington’s nor Franklin’s case has the legend overshadowed the man’s actual, substantial contribution to his country.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of Nebraska’s J. Sterling Morton. Morton is lionized as the founder of Arbor Day. Modern mythology that passes for history these days has taken Morton’s interest in tree-planting and, by emphasis, has exaggerated it to the extent that most people consider Morton a father of environmentalism and the “green” movement, a Johnny Appleseed of the Nebraska prairie. If asked to name another accomplishment Morton made, a person may well ask, “Is there any other?”

Clearly, we don’t know J. Sterling Morton, and that’s a real shame, because such a man — better yet, a state filled with such men — would be equipped to solve the problems currently facing Nebraska and the United States as a whole.

Morton was born in New York and raised in Michigan. He and his young wife migrated to the Nebraska territory in 1854, settling first in Bellevue and, later, in Nebraska City. According to Morton’s biographer, James C. Olson,

“[h]is boyhood in verdant southern Michigan had not prepared [Morton] to accept the barren soddies, baking under the hot Nebraska sun, as a desirable environment in which to build a home and rear a family. Much of the non-political effort of his work on the pioneer Nebraska City News had been to inculcate in his readers an appreciation of the value of trees, and a belief that the soil and climate of Nebraska would produce trees as well as crops of grain and hay. The setting aside of one day each year on which to plant trees redounded primarily to the benefit of the homes of the state. Commercial orchards and groves would not be built up by planting trees one day a year, but one day a year devoted to planting trees about the houses and grounds of the farms of the state would go far toward making the transformation from barrenness to beauty. That Morton had this aspect of Arbor Day clearly in his thinking is evident in all of his writing upon the subject.” (emphasis added).

Although close to his heart, Morton’s conservation and beautification efforts were secondary to his political activities on behalf of his adopted state. And, throughout his life, Morton was very much a political animal.3 But, because his politics are distasteful to modern, Progressive sensibilities, Morton’s true example, his political legacy, has been obscured — and, I think, intentionally so — and replaced with the more palatable image of pioneer environmentalist.

So, what were Morton’s politics? What is his true, political legacy? What can we learn from him?

. . .

I’ll say that again.

. . .

Morton was a Democrat.

(No, I haven’t gone over to the dark side and neither did Mr. Morton. Read on.)

J. Sterling Morton was a Democrat when the Democratic Party — or, at least, Morton’s wing of that Party — still represented the values of classical liberalism.4 As a classical liberal, “Morton opposed federal and state interference in the economic and social life of the American people . . . [arguing] that the role of government in society was that of a policeman. It should protect property and contracts, but not give advantages to any of the players. And, above all, the government should not become a player in the economic game, which was most productively played in an open environment with free and equal competition by all.” (Folsom, pp. 18-19.) Most notably, as a liberty-minded individual, Morton saw the evil inherent in the Progressive movement and opposed it — and its prophet, William Jennings Bryan — to his dying day.5

As a consequence of his liberalism, Morton’s positions on many issues of his day are attractive to those of us who oppose Progressivism in all its forms today. For example:

- Morton argued that taxes should be levied solely to raise revenue, not to advantage one business or class at the expense of another.Consequently, Morton opposed protective tariffs, which he saw as business subsidies. He opposed farm subsidies as well, saying, “[T]hose who raise corn should not be taxed to encourage those who desire to raise beets. The power to tax was never vested in a Government for the purpose of building up one class at the expense of other classes.” (Folsom, p. 24.) Needless to say, he would be appalled at the efforts of this and previous administrations to use the tax code to reward some, to penalize others, and to redistribute wealth overall.

- Morton opposed government welfare and disaster relief in favor of private charity. An example will serve to illustrate Morton’s philosophy in action. In 1874, when Nebraska farmers and ranchers were devastated by a grasshopper plague and drought, Morton rejected calls for government relief. Instead, he formed a private Relief and Aid Society to provide loans on easy terms for the needy. As a result of his personal efforts, “donations of cash, food, and coal came in from the Burlington and Union Pacific Railroads and from banks and entrepreneurs in and out of the state,” and farmers and ranchers were able to outlast nature until crops were, again, plentiful the following year.6 (Folsom, p. 21.) Morton’s beliefs in this regard were severely tested throughout his lifetime, but his persistence in them is vindicated by our current predicament as a state and a nation, a predicament attributable to subsequent generations’ decision to stray from Morton’s principles.7

- Morton opposed Prohibition, arguing that it “invade[d] domestic life, destroy[ed] man’s independence as a free-will agent, and obliterate[d] . . . the sacred rights of property.” (Folsom, p. 2.) According to Morton, “[o]ur right to control what we eat and drink, however imprudent our decisions, is as sacred as our right to choose where we live or what job we seek.”(Folsom, p. 3.) How kindly do you think Morton would have viewed a government mandate to buy health insurance? Any question he’d oppose a broccoli mandate?

- Morton supported sound money. Bryan and his political followers were pushing free silver, which Morton realized would “destabilize America’s currency, wreck the climate for investment, and take the country off the gold standard.” (Folsom, pp. 25-26.) Morton rightly saw free silver as special-interest legislation, putting the government in the position of picking winners and losers, something Morton categorically opposed throughout his political career.8 Is there any doubt Morton would have vehemently opposed the very existence of the Federal Reserve, let alone its manipulation of the nation’s currency and economy? Any doubt that, short of abolition, Morton would have pushed Congress to audit the Federal Reserve and put it on a short leash?

- Finally, Morton reacted to an economic downturn by voluntarily CUTTING government spending. During the depression of 1893, Morton was Secretary of Agriculture under President Grover Cleveland. “Morton carefully studied his Department’s budget and concluded that most of the money it spent was a ‘gratuity, paid by money raised from all the people, and bestowed upon a few people.’” (Folsom, p. 23.) Eager for the government to leave as much money as possible in the taxpayers’ pockets, Morton acted on his own initiative and refused to spend 20 percent of the money allocated to his Department so he could return that money to the federal treasury. (Folsom, p. 26.) Just think what effect it would have on the current federal deficit and the overall economy if the heads of each of the 15 current Cabinet Departments followed Morton’s example! Boggles the mind, doesn’t it?

Clearly, we don’t know Morton. If you’d like to get acquainted with him, I recommend you read the following:

J. Sterling Morton: Pioneer Statesman and Founder of Arbor Day, by James C. Olson

AND

No More Free Markets or Free Beer: The Progressive Era in Nebraska, 1900-1924, by Burton Folsom, Jr.

Images in the post were found at the following links…

Liberty tree image formerly

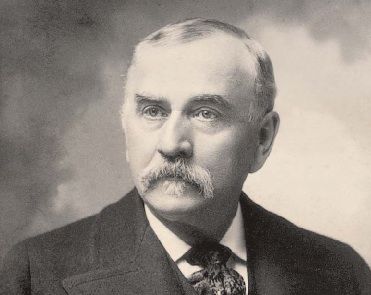

J. Sterling Morton portrait – quote edited out

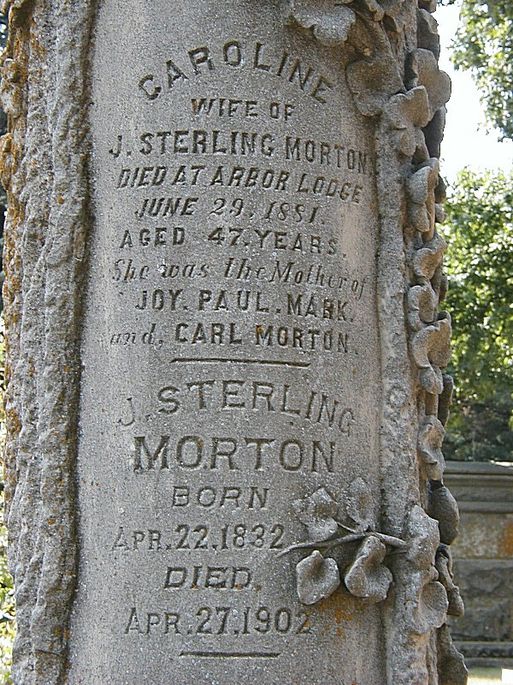

Morton tombstone

- This myth was popularized in a fable written by Mason Locke Weems about 15 years after Washington’s death. A copy of the fable can be found HERE. ↩

- Discussion of Franklin and whether he actually flew the kite or just wrote about it as a possible experiment can be found HERE and HERE. ↩

- Aristotle observed that man is, by nature a political animal. But what is commonly meant when referring to a person as a political animal, and what I mean when I refer to Morton in that manner, is that he was a man whose involvement in politics was so active as to appear almost consuming in focus, at least professionally. ↩

- In his book Capitalism and Freedom (1962), Milton Friedman described classical liberalism as follows: “As it developed in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the intellectual movement that went under the name of liberalism emphasized freedom as the ultimate goal and the individual as the ultimate entity in the society. It supported laissez faire at home as a means of reducing the role of the state in economic affairs and thereby enlarging the role of the individual; it supported free trade abroad as a means of linking the nations of the world together peacefully and democratically. In political matters, it supported the development of representative government and of parliamentary institutions, reduction in the arbitrary power of the state, and protection of the civil freedoms of individuals.” ↩

- Morton once referred to Bryan as a “loathsome pestilence” and to Bryan’s policies as “Bryanarchy,” a clever combination of Bryan’s last name and anarchy. (Folsom, p. 36, and Olson, p. 412.) “With fine sarcasm, (Morton) explained the term “Bryanarchy”: ‘The difference between anarchy and Bryanarchy is that the former believes in no government at all, and the latter believes in no government without Bryan. No government is bad enough, and why any sane citizen should yearn for anything worse, is beyond comprehension.’” (Olson, p. 412) ↩

- This is very similar to something President Grover Cleveland did in vetoing the Texas Seed Bill during his first term in office. Although Morton served as Secretary of Agriculture under President Cleveland, Morton was appointed to his post during Cleveland’s second term and, consequently, was not part of the Cleveland administration when the veto occurred. ↩

- That Morton lived his principles in this regard is clear. Morton’s biographer notes: “Poor people often found their way in financial distress either to Arbor Lodge or the office of The Conservative (Morton’s newspaper), and those who were anxious to aid a needy friend or relative never failed to see the Sage of Arbor Lodge. They seldom, if ever, were disappointed in getting the gift or small loan they sought. Morton, whose political philosophy inclined him to the belief that every man should stand on his own feet, often chided himself in his diary, fearful — though his generous spirit could not have made him otherwise — that he was ‘an easy mark.’ Occasionally, to salve his individualistic conscience, he would insist upon proper business form, and get security for his loan; but while his mind would insist that he must have security, his heart would accept mere tokens, as, for example, the time he loaned fifty dollars to an old soldier, secured by a badge of the Grand Army of the Republic.” (Olson, pp. 426-427.) ↩

- When Morton discovered employees in his own Department of Agriculture advocated fee silver, he reportedly had them paid in silver coins. “In one case, Morton had an employee paid over $172 in silver coins, weighing more than ten pounds, which the man then had to lug home.” (Folsom, p. 26.) ↩

You must be logged in to post a comment.